Vital Organization: Why Strategy Matters

“External success blossoms from internal harmony.”

Brice Montgomery

“If you fail to plan, you plan to fail.” If you’ve spent any time on Pinterest like we have, odds are high that you’ve seen dozens of dubiously attributed clichés like this one. We all seem to intuitively know that planning is important, but many organizations struggle to articulate a clear organizational strategy, likely because they don’t truly understand why strategy matters.

Over the coming weeks, we’ll share tips about how to develop and evaluate strategies for your organization, whether you work with a church, a nonprofit, or a small business. After all, different organizations have different needs and goals, so it is important to approach them accordingly. First, though, it’s critical to understand the big picture reasons that organizational strategy matters.

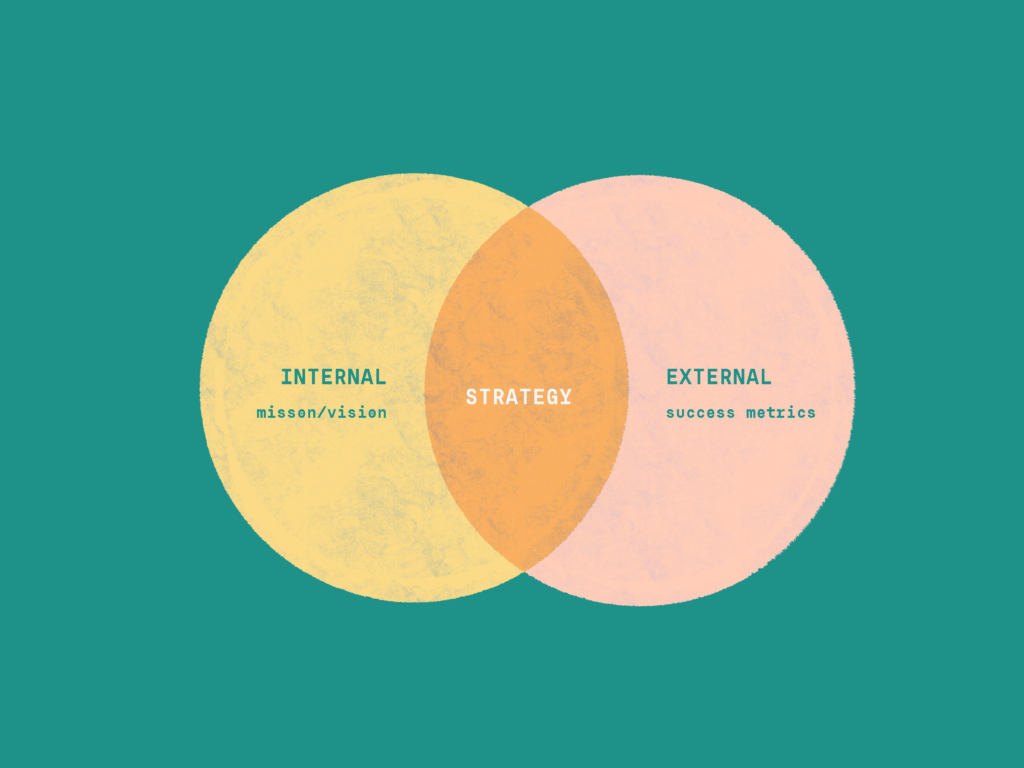

Strategy from the Inside-Out

If you’ve been following our posts on vision and mission statements, you know that an organization is only as good as its guiding principles. An organizational strategy should have clearly articulated internal goals that have external ramifications. To put it another way, external success blossoms from internal harmony. That doesn’t mean that conflict within an organization is inherently a problem—in fact, creative friction can help refine a shared vision.

What this does mean is that your internal structure should act as the infrastructure for your work outside the walls of your organization. It may seem obvious, but you can’t accomplish goals if your organization isn’t equipped to work toward them. That’s why strategy matters. As you begin to evaluate your organizational strategy, first ask yourself whether you’ve been concentrating too much on your impact without cultivating a culture to accomplish it.

Priorities, Priorities, Priorities: Why Strategy Matters for Scope

It’s tempting to fall into what we’ll call “The Cheesecake Factory Conundrum.” Have you seen the Cheesecake Factory’s menu? They have literally hundreds of items, but you’d be hard-pressed to name any item—aside from cheesecake—that they are really good at. Organizations face the same challenge, and each one has to decide whether it will do a few things with care and focus or attempt to bite off more than it can chew.

You can’t do everything. At the end of the day, every day has only so many hours, and your organization has only so many resources. It is better to pick a few critical areas of work than to get carried away with possibilities. This is another reason why strategy matters: it will help you distribute resources where they are needed most, and it will help you place staff in positions that play to their strengths.

Practically, this becomes especially important when unexpected challenges arise. The difference between a good organizational strategy and a bad one isn’t that the former completely avoids problems—it’s that a good strategy lets you pivot without losing momentum.

Who’s Who?: Why Strategy Matters for Staff

Whether you’re just starting out or at a turning point in your organization’s life cycle, one of the most important parts of a strategy is clearly differentiated roles. Particularly in small businesses or nonprofits, people may feel resistant to any sort of hierarchy. After all, an egalitarian structure may differentiate your organization from a large corporation. That doesn’t mean, however, that it’s bad for everyone to have a clear purpose.

If your organization isn’t getting the traction you’re hoping for, it may be time to ask hard questions about the people who are involved. Shared passion for common goals can only go so far, and it’s crucial that everybody on your team is essential. It may be helpful to consider why people first got involved and the degree to which they are still aiding in the initial goal. This will help you gain perspective in a few ways: First, you—and others—may recognize that some people are ready to move on because the organization has naturally shifted in its vision, or second, it may highlight places where your organization has drifted and you need to realign it to your vision.

Winning the Numbers Game

Up to this point, we’ve talked mainly about the big picture reasons for having and evaluating your organizational strategy, but if you want to get really practical—and we think you should—here are some next steps you can take.

Take a long, hard look at where your budget’s going and what kind of results you’re seeing. Insanity might be doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result, but so is bad strategy. Do not allocate resources without first determining a threshold of success for the expenses. In other words, have a plan for what money will accomplish, and be willing to adapt if you don’t see a justifiable impact.

Finally, a common best practice is to use a SWOT analysis—a simple analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, which might affect your organization. Despite their ubiquity, many people get these wrong, so we recommend checking out HBR’s great article on how to do a SWOT correctly.

As always, if you’re interested in getting some support in evaluating or developing an organizational strategy, or simply discussing why strategy matters, we’d love to help. Contact us to chat!